I’ve occasionally thought we need a new version of Flaubert’s book, and Cinderella has made a start. Into the blogroll he goes; better late than never.

So I’m reading Michael Kinsley’s too-clever-by-half piece in Slate on the University of Michigan case, and I happen on this:

Undoubtedly, Alan Bakke [the plaintiff in the 1978 Supreme Court that allowed schools to consider race “as a factor” but disallowed “quotas”] would have been admitted if he had been black. But that’s not the right question. The right question is whether, as a white, he would have been admitted to medical school if all those places weren’t reserved for blacks. The same question arises in the current case, Grutter v. Bollinger…

Figures from a representative year included in court documents indicate that the school [University of Michigan Law School] gets about six applicants for every available place, and that even among those with Grutter’s [Barbara Grutter, the plaintiff] impressive [3.8/4.0] GPA, your chance of getting in is about 1 in 3. Even assuming, implausibly, that every single one of the special-treatment minority students was less qualified than Grutter and would not have been admitted if they were white, that would have improved Grutter’s own chances by about one-eighth. The likelihood that affirmative action done her in is very small.

The facts are not clean enough to suit Kinsley. Unfortunately it will always be impossible to prove that a rejected applicant was kept out of law school by affirmative action, since many admissions criteria are non-objective and the matter is ultimately at the admission committee’s complete discretion. The Supreme Court understood this, and understood that Grutter’s obviously damaged chances of admission were a sufficient grievance, which is why they took the case. The facts will never be clean enough to suit Kinsley.

Kinsley’s math is also lousy. If you increase the spots available by one-eighth, you do nothing for the bottom half of the applicants, who will be rejected anyway. But you do a great deal for the marginal applicants, like Grutter. You certainly increase their chances of admission by more than one-eighth.

Garden-variety sophistry so far. But then:

And while we’re playing “what if,” we should also consider the effect on Grutter’s chances if she found herself competing against blacks and other minorities who had experienced the same variety of advantages and disadvantages as the white candidates in the applicant pool…

And if justice entitles her to the higher chance of admission to Michigan Law School that she would have enjoyed if there was no reverse discrimination, that calculation should also reflect the lower chance she would have had if there was no discrimination of the traditional sort either.

This is the John Lennon School of Legal Reasoning. (It’s easy if you try.) We may as well consider the effect on Grutter’s chances if we all lived in a different galaxy and she found herself competing against silicon-based life forms. Exactly what “variety of advantages and disadvantages” does Kinsley wish us to iron out? I’d wager on affluent, well-educated parents and better elementary and high schools. But why stop there? Why not genetic endowments as well? Some of us were born stupid: where’s the justice in that?

Kinsley is rarely stupid. But he is often slippery.

(Related: John Rosenberg has interesting comments on the same piece. So does Jane Galt.)

Mindles Dreck details how government has gotten huge despite federal spending remaining more or less constant as a percentage of GDP. Steven Den Beste on the real evil computer empire. Jane Galt on file-sharing, the recording industry, the nature of intellectual property, and why CDs are so damn expensive. So how come she doesn’t tell us why jewel boxes are apparently designed to break? Colby Cosh on why his blog is so damn ugly. (Preview: It’s your fault! Disclaimer: It isn’t all that ugly. Really.) Mark Riebling, for the umpteenth time, on domestic security failures, with bonus Times-bashing. Arthur Silber is theist-baiting. In related news, Casey Fahy has a holiday quiz. The Man Without Qualities misdecks the halls. Myself, I’m still trying to figure out what “elbow dust” is in that song from Les Miserables. Europe 2002 = America 1979? Philosoblog on how Chinese philosophers aren’t necessarily versed in Chinese philosophy. That’s affirmative action to you.

Howard Owens, proprietor of a fine blog, gets himself into hot water with a couple of pomo poets. “Poetry must be at least as well written as prose,” said Ezra Pound, and says Howard, and I agree. Howard’s critics, practicing contemporary poets God help us, would not know a good poem if it walked up and punched them in the mouth. One of them, Mike Finley, praises this (scroll to the bottom if you insist on following the link) by Charles Potts. I will spare you most of it; here’s the beginning of the last stanza:

Down a lazy river to the polluted sea

The flotsam jettisons thoughtlessly along,

Contributory to a natural disaster.

“Lazy” is the laziest possible adjective. “Jettison” is a transitive verb, and the accidental association with “jetsam” is doubly unfortunate. “Contributory” would mar a business memo, let alone a poem. Someone who praises this has at best a nodding acquaintance with English.

Another, Joseph Duemer, thinks that Alone, by Jack Gilbert, is a great poem:

I never thought Michiko would come back after she died. But if she did, I knew, it would be as a lady in a long white dress. It is strange that she has returned as somebody’s Dalmatian. I meet the man walking her on a leash almost every week. He says good morning and I stoop down to calm her. He said once that she was never like that with other people. Sometimes she is tethered on their lawn when I go by. If nobody is around, I sit on the grass. When she finally quiets, she puts her head in my lap and we watch each other’s eyes as I whisper in her soft ears. She cares nothing about the mystery. She likes it best when I touch her head and tell her small things about my days and our friends. That makes her happy the way it always did.

This is prose. The reader may insert line breaks where he chooses. They won’t be any better than Gilbert’s, or any worse.

Unfortunately Howard himself goes in for similar stuff. He quotes with favor this bit from Richard Howard:

… Everyone knows my history,

complete with goddesses, islands, all those hoary lies!

I have no tales to tell, I have only

echoes. The real Ulysses puts in his appearance

between other men’s lines, the true Odysseus

shows up in unspeakable pauses, the gaps and blanks

where life hasn’t already been turned into

“my” wanderings, “my” homecoming, even “my” dog!

This is prose too, loosely iambic like most prose, dotted with random chunks of blank verse. The second line and first half of the third form two nearly perfect pentameter lines, and then suddenly the iambs disappear. That’s not a poem, no matter where you break the lines.

Free verse, like all verse, can be scanned. If there’s no proper scansion then it isn’t verse. Free verse is syllabic, with a regular number of primary accents per line — anywhere from one, as in H.D.’s Orchard, to three, as in Wallace Stevens’ The Snow Man; more than three is unmanageable. There is a varying number of secondarily accented and unaccented syllables and an occasional half or double line. It’s real verse, and even without understanding the technical details — consult Yvor Winters’ essay in Primitivism and Decadence, “The Influence of Meter on Poetic Convention,” if you care — a competent reader who takes the trouble to read carefully the two poems I cite will hear the difference.

(Howard comments further. Joseph Duemer replies and so does Mike Finley. Alex Knapp tries his hand at a parody, which is no worse than the real stuff.)

(Update: Blogosphere laureate Will Warren, a poet with actual talent, is retiring. He reminds me a lot of the fine and nearly forgotten 19th century comic poet W.M. Praed. Some of these rhyming haikus are my favorite things of his.)

Here’s an idea: anyone who wants to move to Europe, just let ’em trade their American citizenship for citizenship of any European country, provided they find a willing European, of whom there is assuredly no shortage. Now if we can just persuade the EU to allow it.

In a guest appearance on 2 Blowhards, Colby Cosh suggests that comedy and Middle Eastern speculation gather the most traffic. With that in mind I want to say a few words about liability law.

Everyone agrees that it is crazy for some flaky broad to collect $986,000 on the theory that a CAT scan deprived her of her psychic powers.1 But what is to be done? Depends who you ask.

1. Change the procedures. The Wally Olson school. Olson, who devotes an entire web site to liability excesses, thinks it’s the way the law is enforced, more than the law itself, that creates the problem. He wants a system, like Britain’s, where the loser pays the winner’s legal fees, rather than our current each-pays-his-own scheme. This is attractive but not without difficulties. It would operate especially harshly in the case of small debts; a $100 debt, paid late, could easily grow, once the collection agency is enlisted, to ten times that or more. You also need a pretty complicated set of rules to determine who really “won” in many cases — if, say, $10 million in damages was asked for and $10 was awarded. Britain even has “taxing masters,” court officers whose job, among other things, is to decide nice questions like this.

It is true that Olson’s proposed reforms would keep a lot of frivolous lawsuits out of court. But the fact remains that frivolous lawsuits, because of the state of the law, are very often won, about which loser-pays, or any other procedural reform, does nothing directly.

2. Revive contract. The Peter Huber school. Huber, who unlike Olson is a lawyer, a distinguished one who clerked for Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, takes a more lawyerly approach to the problem. Huber argues that liability litigation flourished as contract withered away. The first blow to contract, struck early in the 20th century, was implied warranty. America had grown rich enough that most people could afford decent food and medical care. Congress passed the Pure Food Act in 1905, and the courts at the same time began to rule that all sellers warranted their products as fit for human consumption, in the absence of any warning to the contrary. Silence on the part of a seller used to mean caveat emptor; no longer, said the courts. (This is a common pattern. Leftist agitator demands a mandate, by law, of a certain good: a 40-hour workweek, a minimum wage, fresh vegetables. Living standards, thanks to capital accumulation, rise to the point where the good is attainable. Said law is passed. Said agitator is lionized as a friend of the people, and history texts trace the good to the law.)

Manufacturers naturally responded with a blizzard of warnings, disclaimers and limited warranties. These were steadily invalidated, at first because of loopholes in their wording, and then, when the wording was tightened up, because of unequal economic power of the contracting parties — the infinitely flexible doctrine of “contracts of adhesion” — and finally because safety disclaimers were “unconscionable” or “contrary to public policy” or “inconsistent with natural justice and good morals,” that is, for any old reason at all.

Huber suggests something he calls “neocontractual law,” which amounts to circumventing the courts instead of trying to reform them. He proposes that companies offer their own insurance directly to customers, providing for a much higher expected payout by eliminating legal fees. If you buy the insurance and take the payout you agree to waive the lawsuit. The beneficiary can always renege, but if the payout is generous enough, and certain, it doesn’t make much sense to do so.

3. End negligence. The Richard Epstein school. Epstein, a professor at the University of Chicago, wrote an essay called A Theory of Strict Liability in which he argues for abandoning negligence altogether and replacing it with strict liability. He adduces some persuasive thought experiments. Consider the famous British tort case of Bolton v. Stone (1951). Miss Stone, passing by a cricket field, is struck in the head by a batted ball and seriously injured. By the negligence standard the batsman was clearly not liable, and the House of Lords so found: only six balls had flown out of the field in 28 years, the risk of harm was not significant, and reasonable care had been exercised. It seems to Epstein, and to me, that the batsman should have to pay notwithstanding. I ran this case by the girlfriend, who is infallible in matters of moral intuition. At first she inquired why I was quibbling over old tort cases instead of looking for a job. Eventually she agreed that, yes, the batsman should pay damages.

Still, this sounds weird. Isn’t it too much liability that got us into our current fix? Not exactly. What got us into trouble is too much judicial discretion, and too much uncertainty. Under the negligence standard everything is conceivably material. In Bolton v. Stone, for instance,

…the plaintiff had to make a case against the defendant on the theory that its cricket grounds were negligently maintained and this opened up a vast range of questions — on the appropriate size for the cricket field; the location of the pitch; the height of the fence; the year the cricket club began to use its grounds; the land use patterns in the neigborhood both at and since that time; the number of cricket balls hit in Mr. Brownson’s neighboring garden; the number hit into the street; the defendants’ views about the safety of their own grounds. It cannot be a point in favor of the law of negligence, either as a theoretical or administrative matter, that it demands evaluation of almost everything, but can give precise weight to almost nothing.

Epstein proposes, essentially, that whoever harms should pay, but he also proposes a rigorous standard for causation, far more rigorous than what now prevails.

Who’s right? They’re all right. Procedural reform is likeliest to be implemented; in fact a good deal of Olson’s agenda is on the Republican platform. There have already been successes for neocontractual law. Since 1981 the State of Washington has sold liability coverage to its public high school athletes for a few dollars a year; not a single case has gone to court. Strict liability in Epstein’s sense may never come to pass; that’s the price for getting to the heart of the matter.

If the Osbourne children, in addition to being rich, famous and idle (you ever see Jack do any homework?), were also attractive, would the show be popular, or even tolerable? I think there would be no show at all. Their looks provide a just sufficient counterweight to keep the Schadenfreude within reasonable bounds.

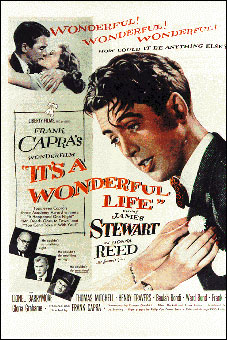

Officially now; and in honor of the holiday let’s look at the all-time British favorite Christmas story, A Christmas Carol, and the all-time American one, It’s a Wonderful Life. These are both dedicated to the remarkable proposition that businesses ought to act as charities. The spirit of Christmas turns out to be altruism.

Poor Ebenezer Scrooge gets probably the worst rap in all of literature. He is of course a banker. Evil businessmen are often bankers, because their activity is too abstract to appear productive. They seem to do nothing but count their money.

Scrooge’s punishment for grousing about giving Bob Cratchit Christmas Day off is a series of supernatural visits, first from his long-dead partner Marley, who has been condemned to wander the world as a ghost in chains. Scrooge asks him why:

“But you were always a good man of business, Jacob,” faultered Scrooge, who now began to apply this to himself.

“Business!” cried the Ghost, wringing its hands again. “Mankind was my business. The common welfare was my business; charity, mercy, forbearance, and benevolence, were, all, my business. The dealings of my trade were but a drop of water in the comprehensive ocean of my business!”

The common welfare was my business. Scrooge, to his credit, is not yet persuaded; he is hard-headed, and requires three more ghosts to bring him completely around. And when Scrooge finally sees what a miserable old miser he has been and how poor Tiny Tim Cratchit will die without his aid, what does he do? He gives Bob Cratchit a raise, not to reward him for efficacy or deter him from seeking other employment, but out of pity and nothing else. Penance for attending to business is drawn from the business itself. The counting house becomes a going social concern.

If Dickens had less charity for his characters and more for his readers, he would dispense with the preternaturally chipper Tiny Tim altogether, or kill him off early at the very least. Oscar Wilde once remarked of The Old Curiosity Shop that one must have a heart of stone to read the death of little Nell without laughing. His views on A Christmas Carol are unfortunately unrecorded.

Frank Capra’s It’s a Wonderful Life is even more wholeheartedly dedicated to the proposition that altruism alone makes life worth living. To summarize, for recent visitors from another planet: George Bailey (Jimmy Stewart) finds Bedford Falls to be a sort of roach motel. His father dies suddenly and he inherits the local savings and loan. He courts and marries a local girl; the losing suitor, Sam Wainwright, leaves town and gets rich in plastics, of all things, twenty years before The Graduate. (For Capra, business success is tolerable, so long as it’s off screen and away from the action.) George’s younger brother Harry enlists in the Army for World War II and becomes a war hero; George sits it out with a bum ear.

Frank Capra’s It’s a Wonderful Life is even more wholeheartedly dedicated to the proposition that altruism alone makes life worth living. To summarize, for recent visitors from another planet: George Bailey (Jimmy Stewart) finds Bedford Falls to be a sort of roach motel. His father dies suddenly and he inherits the local savings and loan. He courts and marries a local girl; the losing suitor, Sam Wainwright, leaves town and gets rich in plastics, of all things, twenty years before The Graduate. (For Capra, business success is tolerable, so long as it’s off screen and away from the action.) George’s younger brother Harry enlists in the Army for World War II and becomes a war hero; George sits it out with a bum ear.

The evil presence of Bedford Falls is the richest man in town, wheelchair-bound Mr. Potter (Lionel Barrymore). (Typically for Capra, It’s a Wonderful Life conjoins a sound morality with a sound physique.) Potter, like Scrooge, is a banker. George Bailey is a banker too. But Potter is a solvent banker, while George runs Bailey Savings & Loan with a generosity of spirit and cheerful disregard for collateral that makes him a popular figure in town and keeps him perpetually on the verge of bankruptcy. George barely staves off one bank run by appealing to the good nature of his depositors.

Potter does his best to put Bailey Savings & Loan out of business, going so far as to offer George an extremely well-paid job as his business manager, but never quite manages. Finally, one Christmas, Potter gets his chance when George’s dotty Uncle Billy absently wraps an $8,000 deposit in a newspaper and hands it to Potter, who keeps it. George, unable to raise the money (he appeals to Potter, who of course turns him down on the grounds that he has no collateral) and faced with financial ruin, decides on suicide.

He is about to jump off the bridge, when Clarence, the bumbling angel, jumps in before him. This is a master stroke. George forgets about killing himself and goes in after Clarence instead. Again, happiness comes from helping others. The two dry off, and then we get the lengthy counterfactual for which the movie is justly famous, the sojourn in Pottersville, the alternate Bedford Falls. I agree with this guy that Pottersville, with its pool halls, dance halls, neon lights and actual prostitutes, looks like a lot more fun than Bedford Falls, where watching the The Bells of St. Mary’s at the local movie house appears to be the only entertainment.

Yet in Pottersville George’s brother Harry, whom George saved from drowning as a boy, has died. Mr. Gower, the pharmacist, whom George saved from accidentally poisoning a customer, has become the town rummy. George’s wife has become a spinster who haunts the library (her other suitor, Sam Wainwright, being mysteriously absent from Pottersville). The townspeople all live in shanties because Bailey Savings & Loan wasn’t around to give them mortgages. (Why Potter should find a poor citizenry more profitable than a rich one is a nice question, but Capra is always a bit vague on business details.) George should live, he finally comes to realize, not for any reason of his own, but for all the happiness he has brought to others.

It will be objected that Scrooge is a sour old miser and Potter is a thief. Yes; and yes. These are two particularly nasty instances of what Ayn Rand used to call “package-dealing.” Instead of attacking the idea of running a business for profit directly, you sneak up on it by associating irrelevant personal characteristics with the one you’re really after. This is especially flagrant in Potter’s case. He is shrewd, and tough, and unpleasant, but nothing marks him as a thief up to the very moment Uncle Billy’s deposit falls literally into his lap. Every time I watch this scene, as Potter hesitates for a second, then hides the money in the newspaper, I half-expect him to give it back. But he never does.

(Update: On aesthetic grounds, Kernon Gibes defends A Christmas Carol (the 1951 movie version, with Alastair Sims) and Colby Cosh defends It’s A Wonderful Life. And I agree with them both, though more with Colby than Kernon. Bad art is useless propaganda.)

Wilde will now appear on a good many blogrolls, including mine (I was gonna do it anyway, I swear), thanks to this. Arthur Silber has some sensible remarks. Now if I could only persuade someone to delink me…

I began writing this post ten minutes ago, and it has been sitting on my hard drive since then, mostly gathering dust, if posts could gather dusts on hard drives.

Now, however, I have decided it’s time to take a stand.

I can no longer include on God of the Machine‘s blogroll any weblog that has provided a permanent blogroll link of its own to the site known as Rittenhouse Review or “RR.”

It is with great regret, considerable lament and substantial redundancy that I have adopted this position — or been forced to adopt this position — as I am normally a passionate advocate of amusing one’s readers. However, it has become painfully clear that RR does not share these values.

I am determined to distance myself in every possible way from their endeavor and those who support it. Lest I be tainted in any way, I shall exclude from my blogroll not only those who link to RR, but also everyone who links to those who link to those who link to RR, and to be on the safe side, everyone who links to those who link to those who link to those who link to RR.

I fully expect to be disparaged with merciless unfairness and obloquy and…what’s that? There won’t be anybody left for me to link to at all? And no one gives a fuck who I link to anyway? Oh. Then never mind.