The unsuspecting reader who opens Emily Dickinson for the first time, in the orthodox modern version, confronts something like this:

I started Early — Took my Dog —

And visited the Sea —

The Mermaids in the Basement

Came out to look at me —

And Frigates — in the Upper Floor

Extended Hempen Hands —

Presuming Me to be a Mouse —

Aground — upon the Sands —

But no Man moved Me — till the Tide —

Went past my simple Shoe —

And past my Apron — and my Belt

And past my Bodice — too —

And made as He would eat me up —

As wholly as a Dew

Upon a Dandelion’s Sleeve —

And then — I started — too —

And He — He followed — close behind —

I felt His Silver Heel

Upon my Ankle — Then my Shoes

Would overflow with Pearl —

Until We met the Solid Town —

No One He seemed to know —

And bowing — with a Mighty look —

At me — The Sea withdrew —

So what’s with the dashes and the capitalization? Nothing, basically. Dickinson’s sentence structure is not loose or complex, and the dashes can be replaced by ordinary punctuation in nearly every instance. This labor is left for the reader who wishes to make sense of the poem. Sometimes the dashes are worse than a nuisance. In the second stanza the dashes surrounding “aground” turn a restrictive clause into a non-restrictive one. The dashes surrounding “too” in the third and fourth stanzas, if read as elocution marks, spoil the rhythm of the poem.

The capitalization is similar. In this poem she mostly capitalizes her nouns and adjectives, with a few exceptions. “Me” is lower-case about half the time. “Took,” a verb, is capitalized (stanza 1), while “look,” a noun, is not (stanza 6). The organizing principle is not apparent because the organizing principle is non-existent. A reader who wishes to make sense of the fine poem that is buried underneath this detritus has to translate first, in a sense. The effort would be more profitably spent reading the poem itself. Many readers, I’m sure, are put off enough not to make the effort at all.

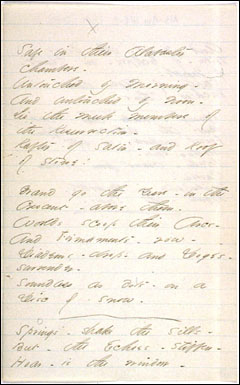

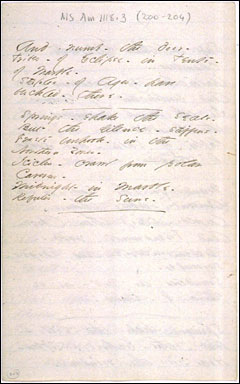

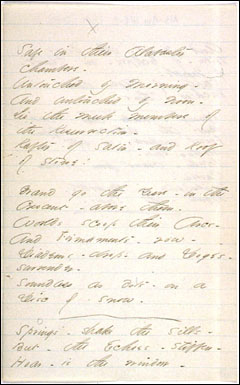

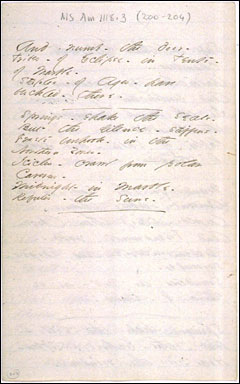

This mess is largely Dickinson’s fault. She notoriously failed to prepare her poems for publication, leaving them instead, hand-written, almost illegibly, in little bundles, or “fascicles” (who was it who said that sounds like Mussolini’s favorite dessert?), in many cases with several variations preserved, among which the put-upon editor is forced to choose. Take a look at this manuscript, of one of her best poems, “Safe in their alabaster chambers.”

Every one of those tiny marks between words is now in the authorized version of this poem as an em-dash, and the man single-handedly responsible for this fact is Thomas W. Johnson, a former Harvard English professor. Johnson did yeoman scholarly service when he published, in 1955, a three-volume edition of Dickinson’s poems, collating all manuscripts, including all variants, and allowing, but also requiring, any sufficiently interested reader to write out the best version of a poem. In 1960, Johnson published a one-volume Complete Poems, containing what he considered to be the “definitive” versions. The dashes have been with us ever since.

Now it should be obvious that a manuscript in this state cannot be published as-is. To begin with, there are three quite different versions of the second stanza. (It might also be a three-stanza poem with two variations on the third stanza; it’s hard to tell.) For Dickinson this is not unusual. More than half of her manuscripts contain multiple versions of at least one word; many of lines, and even stanzas, like this one. There are also multiple manuscripts for quite a few poems, and of course these differ among themselves as well. They need a real editor, not a transcriber.

Johnson usually tries to solve this problem by choosing the last version, based on a dubious analysis of how Dickinson’s handwriting changed as she aged. But she left all of the versions, not just one, and it’s mind-reading to assume, with none of them crossed out, that the last is what she wanted. As Yvor Winters wrote, “The only thing one can do in a situation like this is to choose the best versions; this takes talent, and Johnson lacks talent.” Lacking talent, Johnson attempts to reduce the problem of editing Dickinson to application of mechanical criteria. His criteria always fail to produce the best version and sometimes fail to produce a version at all. This very manuscript of “Safe in their alabaster chambers” defeats him; he ends up offering two versions; he cannot choose.

In the 19th century editors used to edit, often with unfortunate results. A mid-century edition of the works of George Washington renders a small sum of money, “as but a flea-bite at present” in the original, as “totally inadequate to our demands at this time.” By comparison Emily Dickinson received very gentle treatment from her first editors, Mabel Loomis Todd and Martha Dickinson Bianchi, the poet’s niece. They regularized her spelling and punctuation, showed some flair in negotiating the manuscript variants, and otherwise left her pretty much alone. In a dozen or so cases Todd substitutes words for which there is no textual warrant. (Bianchi, her successor, is clean on this score.) She notoriously changes “what a billow be” to “what a wave must be” in “I never saw a moor”; the poem is hopeless in either version. And she actually improves one of Dickinson’s greatest poems, “There’s a certain slant of light,” by changing “heft” in the first stanza to “weight.”

Later critics have jumped all over Todd for this, apparently preferring Johnson’s consistent approach, which wrecks all of the poems. But Todd and Bianchi do the hard work that Johnson leaves to the reader. This is Bianchi’s version of “I started early”:

I started early, took my dog,

And visited the sea;

The mermaids in the basement

Came out to look at me,

And frigates in the upper floor

Extended hempen hands,

Presuming me to be a mouse

Aground, upon the sands.

But no man moved me till the tide

Went past my simple shoe,

And past my apron and my belt,

And past my bodice too,

And made as he would eat me up

As wholly as a dew

Upon a dandelion’s sleeve —

And then I started too.

And he — he followed close behind;

I felt his silver heel

Upon my ankle, — then my shoes

Would overflow with pearl.

Until we met the solid town,

No man he seemed to know;

And bowing with a mighty look

At me, the sea withdrew.

Which one would you rather read?

(Update: AC Douglas comments.)