(Read Part I. Promised tomorrow, three days ago. Tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow. Those who prefer the gossip without the theory should skip to the bottom.)

The “New Critics,” now very old or dead critics, having had their heyday in the 1940s and 1950s, were a diverse group united, sort of, in the belief that the poem was “autotelic,” in the contemporary jargon. The poem was self-contained and to be read as such. Biography in particular was rigorously excluded: to introduce it was to commit what W.K. Wimsatt and Monroe Beardsley called “the intentional fallacy,” which held the author’s intention to be irrelevant to the meaning of a poem. “Critical inquiries,” they intoned, “are not settled by consulting the oracle.”

Now that the Age of Psychology is in full flower, and the work serves mostly as grist for invidious speculation about the life, Wimsatt and Beardsley seem quaint. At least critics back then were still trying to interpret the poem. (It goes especially hard these days with authors whose lives were uneventful, like Emily Dickinson. A quiet life is easy to fill with speculation, and her feminist critics, especially, have not hesitated. Anyone inclined to psychoanalysis could have a field day with the critics of “My life had stood a loaded gun.”)

Yet poems do not float in the ether: some context is relevant. The date of composition matters, surely. Words change meanings. Critics who wish to find in a modern poet the secondary meaning of “come to orgasm” in the word “die” will embarrass themselves, since it disappeared by the 18th century. Words go in and out of favor. Our Hardy poem was written in the 1890s, when “hither and thither” were not archaic as they are now. Grammar changes: the dangling participle, considered illiterate now, is a common construction among learned Elizabethans. (See Greville’s “Down in the depths” for instance.)

If we take the “intentional fallacy” at its word, however, it is just as valid to find a pun on “die” in Wallace Stevens as it is in John Donne, and as valid to criticize Greville for a dangling participle as Wordsworth. Wimsatt and Beardsley are right to prefer public evidence, what is found in the poem, to private evidence, what is found elsewhere; but surely one cannot read private evidence out of the record altogether. (Borges’ little fable about Pierre Menard, who rewrote Don Quixote word for word, but 300 years later, making it a different work entirely, is an excellent joke on Wimsatt and Beardsley, or maybe on me, I’m not sure which.)

Nor are dates a mere matter of grammar and etymology. A Christian poem written in the 16th century is a good deal different from one written in the 20th. Without a substantial grounding in medieval theology and philosophy Dante’s Inferno is impossible to understand. Poems are not composed “autotelically”; how can they be read that way?

Even biographical information has its uses. Hardy was a widower who cherished his late wife and addressed many poems to her. One does not need this information to read “My spirit will not haunt the mound” — to which we will keep returning in this series, I promise — but one’s understanding of a line like “I and another used to know/ In backward days” is surely enriched by the fact.

(And now some New Critic gossip from the fine poet Tim Murphy, who had Robert Penn Warren (did anyone really call him “Red”?) and Cleanth Brooks at Yale: “The first time I met Professor Brooks was when the Warrens took me to his home for Thanksgiving dinner. The house was an 18th century Vermont farmhouse, post and beam, lovingly reassembled in the woods north of New Haven. The beams were about five feet eight off the ground, which was fine for Cleanth and his wife but a headache for anyone else. One guest was the great prosodic theorist, William Wimsatt. At six feet seven, he stooped with chin atop one of the beams, peering down at the proceedings like a bemused owl.

“The last time I saw Cleanth Brooks he chaired my oral examination as Scholar of the House in poetry. Like the other eleven SoH’s, I’d been given my senior year off; and I spent it reading all of Shakespeare twice, writing verse, learning Greek, adding to the twenty-five thousand lines Warren had had me memorize, chasing boys, and doing drugs. Having forgotten all about the oral, I’d dropped acid around 4:00 in the morning. At 8:30 the Dean’s office called: “Where are you?” Tripping my brains out, I ran the four blocks to Strathcona Hall. There sat Brooks, flanked by two assistant profs who hated my guts. For the next two hours I recited Homer, Beowulf, Chaucer, Shakespeare and Timmy, leaving little time for questions. When I left, fearing disgrace, I’m told that Brooks urged that Murphy be given Honors for a year productively spent. Mine enemies dared not demur. The end result of this performance was that a terrible student was lifted from the ranks of the unlettered and granted a cum laude degree. Once more, I had escaped.”)

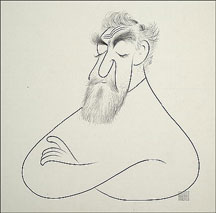

He died just shy of 100, the greatest and best-known caricaturist of the 20th century, and he drew until the very end. It is odd to say he was underrated, but familiarity bred, if not contempt, then more familiarity and when you saw him every week in the Sunday

He died just shy of 100, the greatest and best-known caricaturist of the 20th century, and he drew until the very end. It is odd to say he was underrated, but familiarity bred, if not contempt, then more familiarity and when you saw him every week in the Sunday